* The shocking failures of American arms in 1812 of course led to a reappraisal of the war effort, though the leadership still failed to grasp just how poorly prepared American forces remained for the struggle. Come the spring of 1813, the fighting flared back up again in the Great Lakes region. Battles for Lake Ontario and the Niagara district proved inconclusive, but the Americans were able to drive the British off of Lake Erie with a spectacular naval victory that effectively restored the Northwest to American control. In the meantime, the Madison Administration began to pursue peace negotiations in hopes that American goals might be won at the conference table, instead of on the battlefield -- though the diplomatic exercise went nowhere for the time being.

* Thanks in part to the good news provided by naval exploits, Madison was re-elected that November, defeating New York City Mayor DeWitt Clinton -- also a Republican, but backed by the Federalists. It was hardly a triumphant victory, Madison ending up with a smaller majority than he had enjoyed in the 1808 election, only carrying Pennsylvania and Vermont among the states north of Kentucky and Maryland. The election further undermined political unity for the war, with the Federalists making substantial gains from voters displeased with the bungling of the war effort. They also benefited from public sympathy as a backlash over the mob violence against Federalists.

Madison's re-election still gave him a mandate of sorts for continuing the war. There was no real doubt that he would do so, though headlines from Europe gave the more far-sighted Americans cause for concern. Napoleon had invaded Russia in 1812, only to find himself isolated and forced to retreat from Moscow that fall, a march that all but wrecked his Grand Army. The writing was on the wall for Napoleon; if he fell, then Britain would be free to turn attention on the Americans. Obviously, the Americans would have to win the war swiftly, all the more so because public support for the conflict was so obviously tenuous. Without progress in the fight, support might well evaporate entirely, placing the government in a completely impossible position.

The American failure in Canada during 1812 clearly demonstrated to Madison that changes had to be made if the war was to go on. Navy Secretary Paul Hamilton, described as an alcoholic and often soused on the job, was replaced by the more competent William Jones, a New England shipowner. Secretary of War William Eustis, rightfully the target of criticism for his lack of administrative skills and direction, resigned on 3 December, with Secretary of State James Monroe temporarily running the War Department. Treasury Secretary Albert Gallatin noted that finding a replacement for Eustis would be difficult since the job, with "all its horrors and perils ... frightens those who know best its difficulties."

After searching about, Madison settled on John Armstrong, a New York politician, who began work on 13 January 1813. Armstrong conducted a reorganization in hopes of sweeping out the "dead wood" of elderly Revolutionary War veterans in the top ranks of the Army, to replace them with younger, more energetic officers. The Army central staff was expanded and other reforms were implemented, but there was a failure to seriously address the problems with the clumsy and corrupt contractor-based supply system.

Armstrong was generally competent at his job, often able to recognize and promote promising officers and, in response to a Congressional directive, preparing a manual of "Rules & Regulations of the Army" that was released in the spring. Unfortunately, Armstrong was also abrasive and inclined to bureaucratic gamesmanship, often at odds with his peers and superiors in the Madison Administration, and did nothing to make a notably fractious cabinet any less so. James Monroe saw Armstrong as a rival for the presidency, and was particularly inclined to bicker with him. Armstrong's generals would also learn to distrust him, disagreeably finding themselves caught up in his games.

Early in 1813, Congress authorized 22,000 more troops and, along with a higher bonus for signing up, a raise in pay from $5 to $8 a day to encourage enlistments -- still not enough, $8 was half of what a man could make as a laborer, without the inconvenience and danger of being a soldier. Astoundingly, even though raising troops was proving difficult, the Army refused to accept black soldiers into the ranks, despite the fact that black freemen had fought with distinction in the Revolution. The Navy was not so fussy, generally glad to obtain qualified sailors regardless of skin color.

Congress also, in a burst of what in hindsight could only be judged an excess of enthusiasm, authorized funding for four ships of the line and six frigates. The Republicans may not have liked the idea of a strong military, but they were finally forced to recognize the impossibility of fighting the war without one. The Federalists enthusiastically embraced the naval buildup. Navy Secretary Jones was pleased at the plans for the warships, but he soon understood their impracticability, if he hadn't realized it from the start: it was foolish to think the US Navy either could or should directly challenge the Royal Navy on the open seas, and there was the problem of actually getting the big warships built, fitted, and manned. Jones thought small fast shipping raiders made more sense, and so only pursued the construction of the ships of the line and the frigates to the extent that it made Congress happy. Jones also felt it both practical and important to obtain naval superiority on the Great Lakes, a matter discussed in more detail below, and building up a high seas fleet ran counter to that goal.

Jones understood how problematic obtaining funds for the war effort was. Given the shortfall in customs revenues due to the non-importation act and British attempts to set up a blockade, the government wasn't able to raise enough money. Loans were obtained from private lenders, at rates not to the advantage of the government, to keep things afloat for the time being. The problem was going to get worse instead of better.

* The goals of the American war effort in the north for 1813 were, unsurprisingly, to retake the lands lost to the British in the Northwest and to once again drive into Canada. Matthew Clay, a long-standing congressman from Virginia, neatly summarized in early 1813 the strategic thinking, effectively the same as that which had led America to war in the first place:

BEGIN QUOTE:

We have the Canadas as much under our command as [Britain] has the ocean; and the way to conquer her on the ocean is to drive her from the land ... I would take the whole continent from them, and ask them no favors. Her fleets cannot then rendezvous at Halifax as now, and having no place of resort in the North, cannot infest our coast as they lately have done ... if we get the continent, [Britain] must allow us freedom of the seas.

END QUOTE

The confident tone of this declaration was undermined by the fact that American command of Canada had proven a complete illusion to that time -- and as far as "infestations of the coast" went, the Royal Navy had barely started to make a nuisance of itself to American maritime communities, doing no more than seizing a few coasting vessels. The British, as later events would show, were capable of doing much worse. Of course, past difficulties could be shrugged off as mere bad luck; what patriotic citizen could doubt renewed efforts would prove more successful?

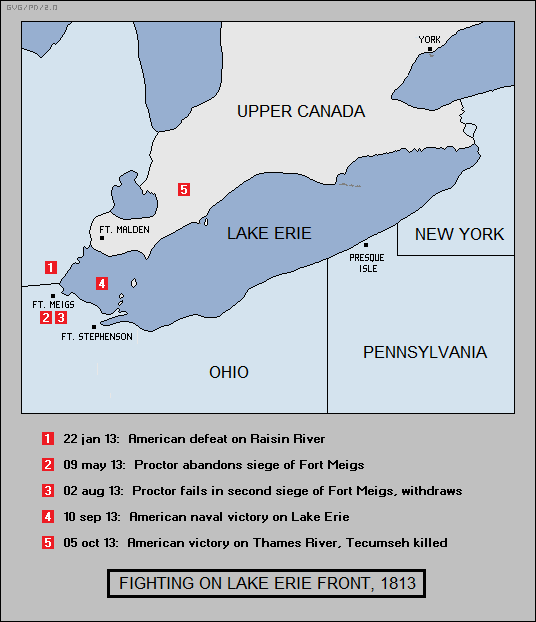

In the Northwest, William Harrison's forces were on the move again in early January, the frozen conditions being better able to support offensive operations than mud. The effort quickly ran into trouble. In January 1813, a detachment of Harrison's force of about a thousand men commanded by Brigadier General James Winchester advanced on Frenchtown, a small British outpost on the Raisin River about 26 miles (42 kilometers) south of Fort Detroit. The Americans made contact with the British and Indian forces on 18 January, driving them out. However, the Americans were complacent, with Winchester proving lax in securing his position and ignoring warnings of enemy preparations for a counterstroke.

The British obtained reinforcements and hit back at sunrise on 22 January. The Americans were in a difficult position, poorly prepared for an attack, with their backs to the river, with deep snow making fighting difficult. They were forced to surrender to the British commander, Colonel Henry Proctor; 300 Americans had been killed and about 500 were taken prisoner. Some of those killed were slaughtered by tribesmen after surrendering, and the battle cry for American fighters in the region became: "Remember the Raisin!" -- though in reality there were plenty of atrocities on both side, with American soldiers taking scalps and engaging in other ugly amusements on occasion.

Proctor had suffered substantial casualties in the battle and did not follow up his success, retiring to Fort Malden; he was promoted to brigadier general and then major general for the victory. On his part, Harrison decided that there was no sense in continuing operations until winter was over, building Forts Meigs and Stephenson on the southwest corner of Lake Erie.

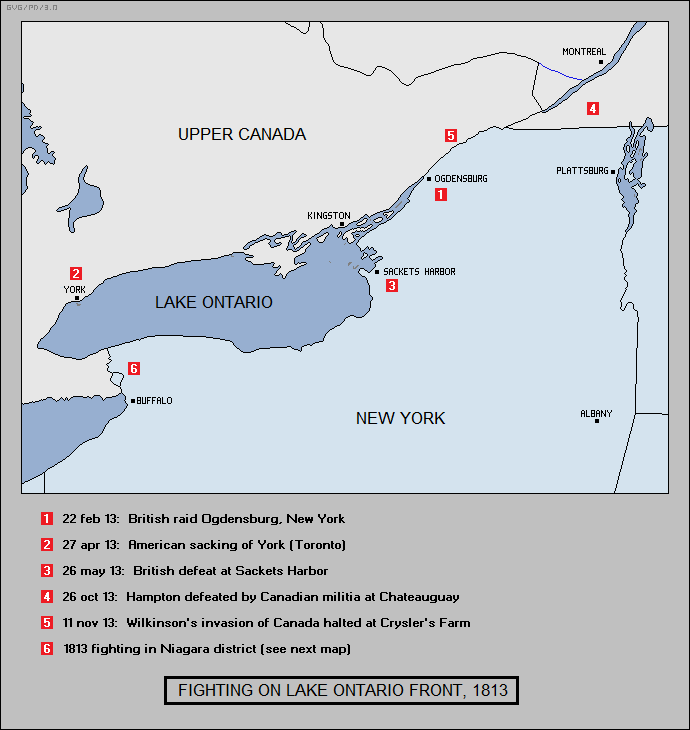

BACK_TO_TOP* The winter made combat in New York State difficult as well, but there were occasional actions, with small-scale raids across the border in both directions. A force under Captain Benjamin Forsyth operating out of Ogdensburg, in New York state on the Saint Lawrence, had been conducting such raids for months, which the Republican papers played up -- though the citizens of Ogdensburg saw Forsyth and his men as nothing more than a gang of bandits whose operations were primarily focused on loot.

The British finally got fed up with the harassment, and so on 22 February a force of 500 Highlanders hit Ogdensburg, advancing across the frozen Saint Lawrence. The attackers cleared out the American troops, to then take off all they could carry and burn what they couldn't. Ogdensburg was a Federalist stronghold and its citizens had never been enthusiastic about the war, preferring instead to engage in peaceful and prosperous trade with their Canadian neighbors. They didn't want American soldiers to come back and upset the applecart again -- and they didn't, the town managing to establish a tactic neutrality in the war.

The idea that an American town could effectively declare itself neutral seems preposterous in hindsight. What made it possible was David Parish, a wealthy landowner in the region. Parish was a Federalist but also an important financier to the Madison Administration, and he was able to attach substantial strings to his loans. Ogdensburg stayed out of the fight to the end of the conflict. When a British officer threatened to burn the town if local authorities did not return several deserters who had taken refuge, the authorities called his bluff -- knowing that if Ogdensburg were remilitarized, that would shut off the pipeline of food and other supplies needed to support British forces in the area. The officer backed down.

Forsyth and his men continued to make a nuisance of themselves from Sackets Harbor. Although Federalists regarded him as a thug and complained about him, he was a hero to the Republicans and ended up being promoted. Forsyth later tried to take action against the border smuggling, only to be shot and killed the next year when an ambush he set up backfired on him. While the late hero was praised in Republican papers, most of the citizens of New York state thought his death no great loss.

* Come the spring of 1813, General Dearborn was entrusted to a new offensive into Canada, leading his forces from their quarters at Plattsburg to Sackets Harbor. The American plan was to move against Kingston; then down to the other end of the lake to York; and finally take complete control over the Niagara frontier. Kingston was the linchpin of the plan, since it was the only really satisfactory harbor on the Canadian side of the lake, and its capture would give the Americans "sea control" over Lake Ontario, cutting enemy communications. Once that was done, York and the British forts in the Niagara frontier would fall into American hands. However, on hearing Kingston had been reinforced, Dearborn and Chauncey hesitated to go for the throat; they prevailed on War Secretary Armstrong to authorize a move against York instead.

About 1,700 troops were loaded up on ships and sailed across Lake Ontario, arriving off York before dawn on 27 April 1813. Dearborn was ailing and so passed command over to Brigadier General Zebulon Pike, well-known as an explorer, memorialized by Pike's Peak in Colorado. The British had a force of about 600 men, holding a strongpoint halfway between the landing and the town. After a tough fight, the defenders were overwhelmed -- but then a powder magazine exploded, killing or injuring many Americans and some British. General Pike was among the dead, having been struck in the head by flying debris. The fight was expensive on both sides, with the Americans losing about a fifth of their number. The surviving British fled to Kingston.

The American soldiers were undisciplined; Dearborn either could not or did not really care to keep them under control, resulting in widespread assaults on civilians, looting, and burnings, the town being generally trashed; a mace of government was part of the loot, not being returned to Canada until the 1930s. The news of what the Americans had done to the unfortunate citizens of York spread rapidly through Canada, helping to rally Canadians against the invaders. The British would remember the matter for repayment later.

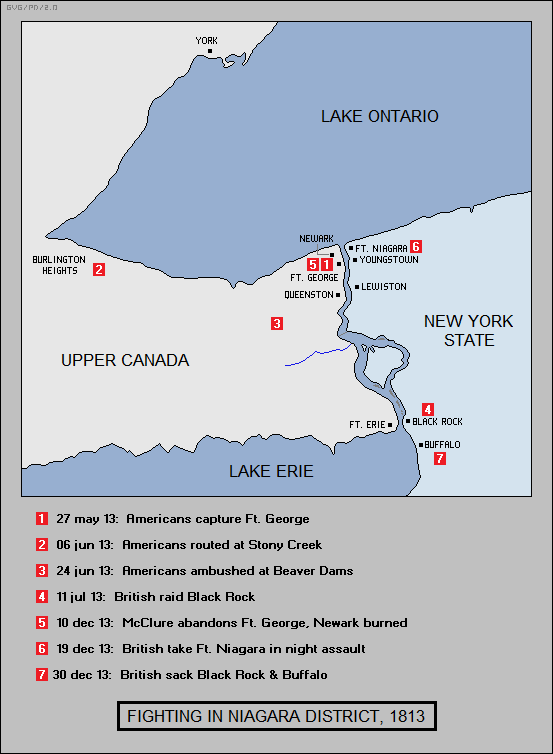

* In any case, after about a week of such rowdiness, the Americans abandoned York, crossing the lake to Niagara for a replay of the previous year's offensive against British positions on the west side of the Niagara River. In the wake of the British humiliation at York, General Sheaffe was replaced in June by Major General Francis de Rottenburg.

On 25 May, Chauncey's vessels moved into position to pound Fort George at the west side of the mouth of the Niagara River, with a landing against the fort by on 27 May by troops under the command of Winfield Scott, now a colonel, and Commander Oliver Hazard Perry, at that time the commandant of the US Navy fleet on Lake Erie. There were about 4,000 American troops involved in the operation, well outnumbering the defenders, and the British gave way; knowing their position was impossible, they abandoned the entire Niagara River and withdrew to Burlington Heights, at the southwest end of Lake Ontario. Dearborn failed to pursue immediately, partly because his troops became engrossed in looting the neighboring town of Newark.

Dearborn's move against York and then the Niagara frontier left Sackets Harbor largely stripped of troops. At Kingston, Prevost decided that presented an opportunity, and took a force of about a thousand regulars and militia across Lake Ontario to grab Sackets Harbor, attacking on the night of 26 May 1813.

The town was defended by over a thousand regulars and militia, under the direction of Brigadier General Jacob Brown of the New York militia. Brown had been born a Quaker and was once a schoolteacher, but had a definite enthusiasm for military affairs. Although the defense had seemed to crumble at first, Brown was able to rally a core of the troops. He set up his men in two lines forward of a fortified battery to meet a landing, and the British came ashore under heavy fire, forcing the Americans back but unable to break their defense. The British suffered heavily in repeated assaults; while they were regrouping to try it again, Brown sent militiamen on a flank attack. That took all the fight out of the British, who then fell back to their ships and departed. Now it had been the turn of the British to suffer a humiliating defeat.

In recognition of his abilities, Brown was taken onto the rolls of the regular Army as brigadier general. However, a Navy lieutenant, believing the battle lost at one point, ordered the stores stockpiled at Sackets Harbor burned. Brown was furious, and Chauncey wasn't much happier with what he saw when he returned with his fleet on 1 June. Chauncey's conclusion was that the security of Sackets Harbor was more important than helping the Army, and he would prove reluctant to provide assistance to Army efforts elsewhere on Lake Ontario from then on.

BACK_TO_TOP* Next, it was the turn of the Americans to suffer humiliations once more. To the east, on and around Lake Champlain, the war had been generally quiet in 1813. The US Navy flotilla on the lake, under the command of Lieutenant Thomas McDonough, had held the balance of power, but on 3 June Lieutenant Sidney Smith, who had been ordered to patrol the northern regions of the lake, confronted a British fortification on a little island named Isle-aux-Noix. Smith had two vessels, the USS EAGLE and USS GROWLER, and with 11 guns each they were the most powerful warships on Lake Champlain. However, the waters were too restricted for the two ships to effectively maneuver, and they ended up being trapped there for several hours, while the British blasted them from shore. Smith finally surrendered, with the two ships becoming the HMS CHUB and HMS FINCH, giving the British naval superiority. They did little with it, Lake Champlain remaining an idle theater for the time being.

The same could not be said of the Niagara district. Dearborn had not been in any hurry to send a force after the British following their withdrawal to the Burlington Heights, finally deciding to move at the end of the month. The American force made camp at Stony Creek, about 10 miles (16 kilometers) from British lines, on the evening of 5 June 1813, with little concern for security. The British hit them with about 700 men in the dark hours of the morning of 6 June, sending the Americans back to Fort George. Although there were no Indians among the attacking force, the British had learned that American soldiers were terrified of Indians, having been raised on tales of savage Redskins and their atrocities; the British went in screaming Indian war whoops that greatly added to the panic of the defenders.

Following this fiasco, the fighting settled down to a sequence of back-and-forth raids. Dearborn sent out a party of about 600 men about two weeks later to attack a British forward position, but the British had got wind of American intentions -- according to legend, thanks to a Canadian woman named Laura Secord, 38 years old, whose house had been occupied by American officers. The unwanted visitors talked too loud and too freely, and so she walked 20 miles (32 kilometers) to pass on American plans to the British. The Americans were ambushed by a smaller force of British and Indians at Beaver Dams near Queenston on 24 June, and forced to surrender. Secord became a heroine, Canada's answer to Paul Revere, though in fact the British already had intelligence on American intentions before she reported what she had heard to them.

On 11 July, a British force raided Black Rock, driving out the defenders to then torch buildings, supplies, and a vessel. The Americans organized a counterattack and drove the British off in their boats, inflicting painful casualties on them. It amounted to nothing much in the bigger scheme of things, with the American war effort in the region continuing to go nowhere in any hurry. Dearborn, still ailing, resigned from the Army on 15 July. Disease was in fact making life miserable for both sides on the front. Indeed, over the course of the war disease would claim several times more casualties than combat.

* There were no more serious confrontations in the Niagara frontier region for the next five months, with the performance of American arms there having proven only somewhat more impressive than that of 1812. An attempt on 28 July by Winfield Scott and 250 troops to perform an amphibious raid on a British supply depot at Burlington Heights was called off before landing, since the British were fully aware of the move and were entirely alert; even Scott, never one to turn down a roaring good fight, judged it suicidal.

From 7 August, there was a skittish duel between Chauncey's and Yeo's ships off of Fort Niagara that went on for several days, as each commander waited for winds that would give them the advantage. Chauncey lost two of his larger schooners, the USS SCOURGE and the USS HAMILTON, early on 8 August when a storm came up and the top-heavy vessels capsized, with most of their crews drowned. On 10 August, the confrontation ended when the British managed to capture two of Chauncey's smaller schooners, the USS JULIA and the USS GROWLER. That was all there was to the naval fighting in the area for the time being, the Americans having got the worst of it.

BACK_TO_TOP* Along with the mixed performance on the battlefield, the leadership in Washington was demonstrating no great diligence in the direction of the conflict. The core problem remained finances: while the loans the government had obtained did manage to keep things going over the short term, there was no getting around the fact that, as things were, over the long run there was no way to fund the war. That meant more taxes, but in Congress, as one observer put it, "every one is for taxing every body, except himself and his constituents."

Still, despite the Republican loathing for "internal" taxes, it was either impose taxes or be forced to give up the fight, and the Republicans were too far into the struggle to give it up at all easily. In July, to much public astonishment, the Republicans pushed through a tax program designed to raise $5.5 million for the government -- though it wasn't to go into effect until the end of the year.

* While the Madison Administration struggled to obtain money to continue the war, it also investigated means of ending it. In March, the Russian government had offered to mediate negotiations between the British and American governments, and Madison had accepted -- to no surprise, the American government had been trying to send a message to Britain for negotiations from the outset of the conflict. Treasury Secretary Gallatin, who had tired of the infighting in the cabinet, asked Madison to be on the peace commission; the commission also included Senator James Bayard, a Delaware Federalist, and John Quincy Adams, who was currently in Saint Petersburg as America's first ambassador to Russia.

Gallatin was an extremely competent man, often labeled a genius, and Madison was reluctant to part with his services; the president officially retained him as treasury secretary, with Navy Secretary Jones to cover for Gallatin in his absence. That awkward arrangement met with bitter opposition in Congress, largely because Gallatin had many enemies there who wanted him out of the cabinet. He never would return to his old job. In any case, Gallatin and Bayard arrived in Saint Petersburg in July; the three commissioners accomplished little for the rest of the year, the Russian government being distracted by other matters, and the British showing no interest in Russian mediation.

Congress adjourned in early August, somewhat to Madison's relief, his dealings with the legislature for the year up to that having been characterized by almost unrelieved antagonism and confrontation. Earlier that summer, Madison had been struck by a serious illness that put him in bed for five weeks and almost killed him. To be sure, although the administration hadn't got all of what it wanted from Congress, the legislature had in the end been supportive of the war effort, but the support was obtained in only the most painful fashion.

* Although the war in the Northwest had gone better for the Americans in 1813 up to that time than it had in 1812, the conquest of Canada still remained a mirage. One of the difficulties was that the Americans hadn't been able to obtain control over Lake Erie and Lake Ontario, allowing the British to ship forces and supplies.

The British were slow to take advantage of their situation, partly because the winter was severe and the spring damp, bogging down movement in the mud. In late April, British Major General Proctor moved against Fort Meigs, leading a force of about 1,500 consisting of British regulars, militia, and Indians under Tecumseh. They brought the fort under siege from 1 May; after a few assaults that failed to break the American defense Proctor, his men increasingly ailing and insubordinate, decided to call it quits and departed for Fort Malden on 9 May.

Proctor was still under pressure to act; somewhat for the lack of anything more constructive to do, he took another stab at Fort Meigs, his force putting it under siege from 20 July. This siege was even less resolute than the first, and the British finally departed on 28 July. He then turned on Fort Stephenson, but though the defenders -- about 160 American regulars under Major George Croghan -- were greatly outnumbered, the fort itself was very stout, as the British discovered when they threw themselves at it on 2 August; the British were badly bloodied, the Americans hardly hurt. Proctor withdrew once more, his reputation with his troops and the Indians having suffered badly.

William Harrison's reputation suffered as well, since he had become timid thanks to grossly inflated estimates of Proctor's strength and had done little as the invaders raided the region almost unopposed. Harrison had even ordered Croghan to evacuate Fort Stephenson and burn it, but Croghan was made of tougher stuff and decided to hold his ground. Harrison didn't attempt to relieve Fort Stephenson, and let the British withdraw back to Fort Malden unmolested.

BACK_TO_TOP* In the meantime, except for the interval spent supporting Dearborn, the 27-year-old Commander Perry had been working at Presque Isle to complete and fit his warships. Perry's resources were not substantial and his nominal superior, Commodore Chauncey, did little to assist; Perry had particular problems finding sailors for his ships, barely managing to beg enough warm bodies from Harrison to build up minimally-skilled crews. However, by the greatest exertions he managed to get things working.

The Royal Navy had been keeping an eye on Presque Isle, with Commodore Robert Barclay, in charge of the British fleet on Lake Erie, stationing warships offshore in anticipation of an American move. One of the problems for Perry was that there was a bar across the mouth of the harbor at Presque Isle, and there was no possibility of getting his larger ships over it unless all their equipment and guns were removed. At the end of July 1813, Barclay's ships withdrew to resupply and refit, apparently on the assumption that Perry would not be able to get his own ships into deep water before the British came back.

Perry took advantage of the British absence to get a substantial part of his force over the bar in four days; when the Royal Navy returned, they found the American vessels lined up and waiting, with the 20-gun brig USS LAWRENCE prominent among them. The LAWRENCE was intimidating, more powerful in theory than anything Barclay had available -- but there was less to things than met the British eye, since the LAWRENCE hadn't been rearmed yet and was, despite its menacing posture, entirely helpless. Of course, Barclay didn't know that; he swallowed the bluff and ran off back to safe harbor at Fort Malden. Perry managed to get the rest of his force, including USS NIAGARA, sister ship to the LAWRENCE, across the bar, and in doing so had achieved effective American control of Lake Erie.

However, as long as Barclay's fleet remained in existence the Royal Navy could challenge American dominance on the lake. Perry sailed his fleet to Put-in-Bay on southwestern Lake Erie, near Forts Meigs and Stephenson, blocking British access to Fort Malden. British forces were going to be starved out sooner or later, and so Barclay was forced to act. On 9 September 1813, Barclay sent out his fleet of six vessels, the most powerful being the 19-gun HMS DETROIT; Perry met him the next day, 10 September, with nine vessels, the most powerful being the LAWRENCE and NIAGARA. In principle, with 20 guns each these two warships were more powerful than anything Barclay had, but in practice all but two of the guns on both vessels were "carronades" -- essentially sea-going howitzers, lightweight and fine for throwing out iron, but not capable of throwing it very far.

The fight between the two little fleets went on for three hours; it was an ugly slugfest, fought at close quarters without much finesse, the crews on both sides of the battle being too unskilled to perform sophisticated naval maneuvers. Each side dealt out and took severe damage, with men cut down in scores; when the LAWRENCE could fight no more, Perry took a ship's boat over to the NIAGARA and resumed command from there. Finally Barclay, who had been badly wounded, could stand no more, and surrendered his fleet. Perry then famously reported to Harrison: "We have met the enemy and they are ours." The Americans had gained complete control of Lake Erie, with Perry becoming one of the heroes of the war. He and his men were generously awarded prize money by the grateful government.

* That left British forces in the region dangling, and so Proctor was forced to abandon Fort Malden and Fort Detroit, planning to march to the British base at Burlington Heights or some alternate position on Lake Ontario. Proctor pulled out on 24 September, torching all he could not take with him.

General Harrison had been reinforced by several thousand Kentucky militia and a regiment of mounted Kentucky riflemen under Colonel Richard M. Johnson. Perry shuttled Harrison's forces across Lake Erie to land them on the shores not far from Fort Malden. The British were gone before the Americans came; Harrison was not quick to pursue since he had no wagons or horses, and he also needed Johnson's mounted regiment, which had taken the overland route to the landing. Johnson hooked up with Harrison on 1 October, with a force of 3,500 men moving out the next day.

Since the British had a week's head start, Harrison saw no prospect of overtaking Proctor, but the British were moving over rough terrain, were accompanied by women and children, and were loaded down with a good deal of baggage. The Americans quickly caught up, with the British forced to turn and prepare for a fight on 5 October, taking up a position on the Thames River not far from Moraviatown. Harrison hit the British with cavalry charges that overwhelmed them, the energetic Commander Perry being one of the cavalrymen; the British were routed and many prisoners were taken. Proctor managed to get away, but his military career was effectively finished. Tecumseh was killed in the battle, with Kentuckians flaying him -- or something they believed was him -- for trophies. The Americans pillaged Moraviatown and then withdrew to Fort Detroit, where Harrison held pow-wows with local chiefs, concluding peace agreements that put a general end to the fighting in the Northwest.

The Americans had effectively regained control of Michigan Territory and erased their humiliation in the region the year before by handing the British a stinging defeat -- the Battle of the Thames being particularly celebrated in the newspapers because of the killing of the dreaded Tecumseh. Tecumseh's effort to unify the tribes had been finally put down, with the Americans keeping the upper hand in the region without serious challenge from that time on. British ambitions to restrict the Americans in the region had been frustrated, as it would turn out permanently. The American government and the Republicans had been in need of real victories; Perry and Harrison had delivered them. However, the vision of the conquest of Canada remained as distant as ever.

* As far as the battle for Lake Ontario went, on 28 September 1813 Chauncey got into a shooting match with Yeo's warships on the open water, with the British taking somewhat the worst of it. The British withdrew and formed up a defensive line at Burlington Bay; Chauncey decided not to press them. The British finally sailed back to Kingston, with Chauncey in cautious pursuit and failing to make contact -- though the American fleet did come across a flotilla of seven Royal Navy schooners, with only one getting away, another being sunk and the rest captured. Two of the schooners captured were the JULIA and GROWLER, which had been taken from the Americans in August. For the moment the Americans had the upper hand on Lake Ontario -- but as long as Yeo's fleet remained in existence, Chauncey had no reason to think that was a permanent state of affairs.

BACK_TO_TOP