* Dualists often insist that machines can never be truly intelligent -- saying that no matter how humanlike and aware they seem, they will not actually have conscious experiences, or what are called "qualia". This is not an idea that tolerates close examination, being based on failure to understand the empirical and observational foundations of science. That misunderstanding leads to the absurd result of the "philosophical zombie": a being that acts perfectly human, but which isn't conscious.

The discussion of the human mind in this document so far was based on an implicit assumption: that when we perceive something, remember something, or think something out, those are conscious behaviors -- as opposed to unconscious behaviors, like reflex actions. We know this is true for ourselves; we assume that it's true for everyone else. It would be absurd for Alice to ask Bob: "Are you really conscious?" Bob's answer would rightfully be: "What sort of silly question is that?!" -- and the conversation would be over.

However, suppose we have a machine that also perceives and remembers things, thinks things out, and can conversationally communicate with humans as well, or better, than a human? If we assume that the people around us who act like they're conscious really are so, then why shouldn't we assume the machine is?

This is a fundamental question about the mind. Dualists will almost always answer, without hesitation: "No, the machine cannot be conscious." If we have a robot that seems to act human, then it must, they say, actually be some sort of a mindless zombie. Dennett called this response the "zombic hunch" or "zombie hunch" -- though that wasn't entirely accurate, since few call it a hunch, instead asserting it with absolute conviction, as if any other answer is out of the question. To a cognitive pragmatist, this response is baffling: "Why not? What's the machine missing?"

What it is missing, according to dualists, is "qualia" -- that's plural, the singular is "quale", pronounced "kwah-lay" not "quail" -- the essence of what is sometimes called "phenomenal awareness".

The idea of qualia goes back at least to the 17th-century English philosopher John Locke (1632:1704), one of the intellectual ancestors of Hume. The first use of the term in its modern sense was in a 1929 book by American philosopher Clarence Irving Lewis (1883:1964), and it remains in widespread circulation as a pop-philosophy notion. The question of qualia is: when Alice sees a blue sky, white clouds, and green grass, how does she know that Bob sees the same colors? What if what Alice sees as blue Bob sees as red, white as yellow, green as blue? In other words, how does Alice know that Bob's qualia aren't "inverted" from hers? In short, what is it that a person actually sees as a personal experience?

The idea of qualia is intuitively plausible; the problem with it is that it does not, cannot, go anywhere. Suppose, as a thought experiment, engineers come up with a pair of goggles that, supposedly, allows Alice to see the world as Bob sees it. She puts on the goggles and says: "Bob, you see the world entirely differently from me! You see yellows where I see reds, you see purples where I see pinks!"

Bob replies: "Gimme those goggles!" -- and puts them on, to protest: "This isn't how I see things at all! It's got yellows and purples mixed up with reds and pinks!" The idea of Bob somehow being directly hotwired into Alice's mind is nonsense. There's absolutely no way to test the goggles. Engineers have a saying: If you didn't test it, it doesn't work; and if you can't test it, you'll never know if it works.

It is true that colors have a perceptual aspect, our color perception being under the control of our three-receptor (red-green-blue) color vision system. However, there's no serious ambiguity when we use the word "blue", any more than when we use the terms "meter", "kilogram", or "second" -- all of which are arbitrary descriptive measures of the real world, meaningless except as commonly-accepted conventions. We have much the same sort of convention with the "color chips" used to categorize different shades of paint.

Suppose that Alice is asked to visualize a ball bouncing in a box with transparent sides. Sure, she can do that. Make it a red ball? Easy. Now suppose she's asked to visualize a dozen balls, all of different colors, bouncing around in the box. All she can actually do, in that case, is imagine "a bunch of balls" with no details; and then imagine, one at a time, a ball of a particular color. Not incidentally, some people claim they dream in color -- but no, they're not really watching pictures of any sort, colored or monochrome, in their heads. It just "sorta" feels like it.

The abstract of a dozen bouncing balls in Alice's head is all she "needs to know". If she were asked if she could visualize them, she would say: "Of course I can." Yeah, all she really has is a general idea of a jumble of excited balls, with no detail, but so what? As long as she knows what's going on, she doesn't need to worry about the specifics. She could easily sit down at a computer and draw out the scene of the bouncing balls, in color, using a paint program -- never mind that she's not copying from a picture in her mind, instead working from a list of abstracts, and realizing the specifics of the image as she goes along.

Anybody who's ever done artwork knows the experience of watching the art image emerge from the raw material of the original abstracted concept, being tweaked until it looks "just right" -- possibly looking far better in the realization than expected. However, the effort may also end in frustration, if the abstracted idea proves unworkable in the real world: "That doesn't work as well as I thought it would."

The bottom line is, yet again, that the stream of consciousness is not a Cartesian theater. Qualia are, in effect, "frames" from the Cartesian theater -- to believe in qualia is to inescapably believe in the Cartesian theater -- but there is no Cartesian theater. Alice has absolutely no problem recognizing colors, no more than any other properly functioning person does. Both Bob and Alice agree that the skies are blue, and others agree with them; it's an unambiguous, objective fact that the open daytime sky is blue. Asking if Bob's "blue" is the same as Alice's "blue" is an intractable question: that is, it has no answer, and nothing can be done with it.

In other words, the notion of "inverted qualia goggles" is a "ridiculous thought experiment (RTX)": it superficially makes sense, but under examination, it proves incoherent and silly. We do know that there are people who don't see colors the same way the rest of us do; they're known as "colorblind", a condition easily tested with an appropriate color chart, and which poses no mysteries at all. People with normal color vision can get a very good idea of what colorblind people see, using color photographs that have been filtered to remove the colors the colorblind can't see.

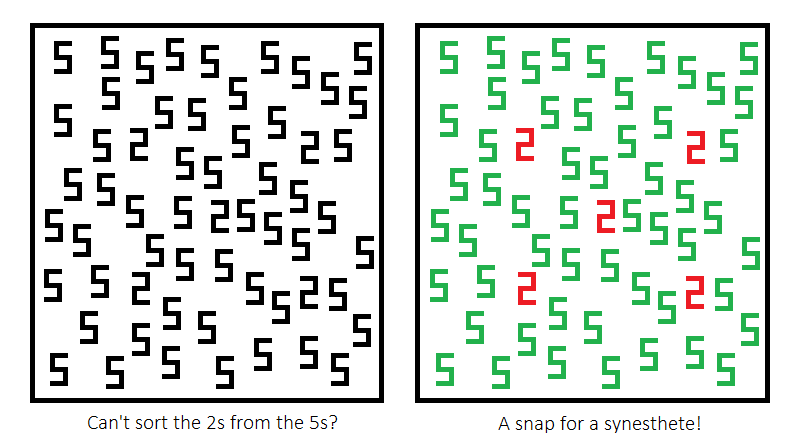

Going a step further, there are people known as "synesthetes" who -- it seems due to some additional brain wiring -- have various sorts of scrambling of sense perceptions. They may, for example, perceive colors associated with sounds, or tastes associated with the reading of words. Synesthesia is so extraordinary that it was once often dismissed as a delusion or a fraud, but careful tests, as per Dennett's heterophenomenology, show synesthesia is for real; synesthetes who link colors to numbers can easily scan through a jumbled page of numbers, and effortlessly pick out a particular digit from its "color code".

Are the "qualia" of synesthesia entirely beyond the ability of the rest of us to grasp? We can't be a synesthete, any more than Bob can be Alice -- but we can easily play at synesthesia:

We do know what it's like to be a synesthete, because they tell us what it's like. Heterophenomenology works.

Even if qualia are accepted, it's hard to show the idea is of any consequence. There's the case of thermal infrared imagers, often used by the military, in which gradations of brightness in the image are proportional to how hot the parts of an object in the image are -- incidentally, such imagers can typically be switched from "hot is bright" to "cold is bright", some things being more easily seen in one mode than the other.

In any case, a thermal imager yields an image very unlike that seen in normal vision; but those who use such devices on a regular basis have, with experience, no problem making out the elements of the image. If Major Harvey sees a target in thermal infrared on a cockpit display, neither he, nor anyone he reports the matter to, has much reason to care that it doesn't look like the same image taken by a daylight camera.

Taking that thought a bit further, suppose that Bob gets a blow to the head, and suddenly ends up with inverted qualia, his yellows and purples mixed up with reds and pinks. He would be very confused for a time -- but he would gradually get used to it, in much the same way that users of thermal imagers get use to the vision of the world in infrared, and in a year or two would be entirely adapted. In ten years, he might well forget what the colors used to look like.

Not at all incidentally, this is another RTX: there have been cases of people losing color vision due to a brain injury, but no reported cases of inversions in color perception. Possibly it happens, but nobody ever notices? Yes, that is being silly. Maybe it happens all the time to everyone, without anybody getting wise? That's sillier.

The notion of qualia also applies -- or more accurately, no more really applies -- to taste. Suppose Alice likes baked salmon, while Bob loathes it and finds it revolting. Is this a question of whether the two have the same taste perception, but different preferences? Or if the two have different taste perceptions, and so different preferences? It's another intractable question; the least burdensome assumption is that salmon tastes much the same to everyone, that people just may have different preferences.

Besides, during our lifetimes, our taste preferences may change; we may learn to like foods we once did not, or dislike foods we once were fond of. We may change back and forth on some foods; when we're ill, we may like some foods that we normally don't like when we're well, and go back to disliking them when we recover. In all instances, aside from the dulling of the sense of taste with age -- which is why older people tend to rely more heavily on spices -- we don't think the food tastes entirely different, we just decide we like it or don't like it. We have no more reason to assume that foods have a dramatically different taste to others, and it's making up a useless difficulty to assume otherwise. If both Alice and Bob like chocolate, nobody is particularly interested in asking if they had a different perception of it.

BACK_TO_TOP* Dualists are inclined to object to Dennett's heterophenomenology, saying that subjective reports cannot be used as objective data, since they can't communicate qualia. OK, so what? Suppose Alice gives a literary description of, say, a sunset:

QUOTE:

The evening was warm, a bit humid; there was little sound, except for the occasional passage of a car along the street, and the distant roar of a lawn mower. The nighthawks had come out as the Sun went down, flitting through the sky to catch insects. There was a scattering of clouds that became brightly illuminated in golds by the last light of the Sun; to fade to reds, then to bluish shades of gray as darkness crept up on them.

END_QUOTE

Few would have any problem visualizing the scene from this description. Neither the writer nor any reader would give any thought to pointless notions of qualia inversion. A dualist might object to the description, calling it inadequate, to which the response from a pragmatist would be: "Explain to me exactly what's missing, so I can add it in." In the absence of any explanation, the writer would have no cause to make any changes.

What's missing? Dehaene provided an insightful definition of qualia as "pure mental experience detached from any information-processing role" -- which in terms of the current example, is like a dualist asking Alice: "Did you see the sunset?"

With the reply: "Of course I did, I just described it to you."

"But what if you just thought you saw it?"

"You don't make any sense." How could Alice see a sunset, report on it, and not really be conscious of having seen the sunset? What cause would anyone have to say she didn't? There's no Cartesian theater in Alice's head, instead sets of abstracts that Alice aggregates into a scene, and reports on.

The question never occurs to literal-minded Bob. If he cannot directly hotwire himself into Alice's mind, he has no problem listening to what Alice tells him, and so acquiring an understanding of her conscious experience. If Alice tells Bob about the sunset in a clear and detailed fashion, that does the job for him.

Now suppose we ask a robot, named Robby, to report on a sunset. The response would be like:

QUOTE:

It is now 1836 hours; the Sun disappeared beneath the horizon five minutes ago. The temperature is 18 degrees Celsius, the humidity is 75%; there is partial cloud cover, but no appreciable breeze. It will be fully dark by 1900 hours. Moonrise will be at 2134 hours.

END_QUOTE

Does Robby actually perceive the sunset? Of course he does, he just described it in dry, clinical detail. There's no more basis to say the robot didn't really see the sunset than to say that Alice didn't really see it. To be sure, the two descriptions are clearly different, reflecting very different minds -- a matter on which much more is said later.

BACK_TO_TOP* The notion of qualia is closely related to the alleged mind-body problem. From the point of view of the sciences, they're both idle notions. The claim that they have scientific significance only reflects a failure to understand what the sciences are all about.

Science is entirely based on reliable observations; if we monitor a certain physical brain activity in a subject and the subject reports a certain conscious experience, then we effectively understand the phenomenon. Yes, we could trace out the physical brain activity in more detail, but it's just like the tale of the mechanical clock:

A scientific theory is no more or less than a framework, derived from reliable observations, to determine predictable causal relationships. The tricky thing is that, as Hume pointed out in developing his skeptical-empirical philosophy, cause is not really a property of an object. We don't observe cause; instead, we observe causal relationships, one thing happening after another.

Hume famously used the example of billiard balls: how would we know what they would do in collisions, unless we observed what they did in practice? Why wouldn't we expect the incoming ball to simply bounce back, while the other stays motionless? Why wouldn't both stop on the impact? Expectations be hanged; to know about the interactions of the billiard balls, and other mechanical interactions, we had to observe them. Those observations led to the development of Newtonian -- classical -- physics as a model to organize the observations, and use it to predict what will happen in future mechanical interactions.

There is nothing in Newtonian physics that we would know to be true, except that it is empirically observed to be true. Indeed, it's not necessarily obvious from observations exactly how things do work; Hume's example of the collision of billiard balls is a highly controlled situation, using balls of uniform weight, density, diameter, hardness, and roundness moving on a smooth flat surface. That's why the collisions of billiard balls make such good examples in elementary physics courses, it's a neatly controlled scenario, with the confounding influences screened out. Were the circumstances not so controlled, the results might not be so obvious.

Once again, when Alice was born, she had not a single fact of the world in her head. Nothing was obvious to her at her birth, and things that became obvious to her were only obvious because they were what she experienced. The "commonsense physics" she and other children acquire still remains loaded down with misleading ideas. Teachers presenting elementary physics to freshman college students are generally careful to point out that many popular notions of how the world works are erroneous, in fact sometimes backwards of the way things really work. Indeed, nobody had a sensible grasp of the way elementary physics works until the era of Newton; it is not something that is intuitively obvious, except to trained intuition. Our commonsense physics is, to a degree, an illusion, not necessarily how physics actually works.

Incidentally, the fact that Alice lacked a world model at birth helps explain why we remember little or nothing of our infancy. We literally did not have any idea of what we were looking at, and only slowly sorted it out. Some claim they have detailed memories of their infancy, or even of being in the womb. Such claims are like those of memories of past lives: never honestly provable, not supported by any hard evidence.

When Alice was in the womb, she was effectively sedated, somnolent, since it would not do to have her be too active before her birth, and there's no useful actions she could take, either. To the extent that she felt or heard things, she had no context, no world view, to make any sense of them. Once she was born, she had a suite of emerging instincts, but in terms of concepts was a blank slate. She did not understand a single word, and had no facts about the world; she had a flood of incoherent perceptions, but literally had no idea at the outset of what to make of them. She was further limited by the fact that her brain was still under construction; her brain doubled in size in her first year, reaching about 90% of full size by age five. Growth became more gradual after that, to effectively cease by early adulthood.

* Anyway, Hume's analysis of causality led him to a subtle notion that he called "necessary connection" -- which, once understood, reveals the fundamental misunderstanding that leads to dualism, along with its trappings such as the mind-body problem and qualia.

The misunderstanding starts with the old expression of "correlation is not causation". As Hume pointed out, this is only a partial truth: all causation is correlation, and nothing but correlation; it's just that not all correlation is causation. If we observe the same correlation of actions happening consistently and we carefully sort out confounding effects, then we can assume the correlation is a causal relationship, and create a theory, a model, to predict what will happen under the same circumstances in the future. If we find exceptions to the correlation that can't be explained by confounding effects, then the correlation is not causation.

This eliminative process -- what's now called "induction", though Hume didn't use the term, confusingly calling it a sort of "moral reasoning" -- doesn't prove any causal relationship. A causal relationship can't be proven like a mathematical proposition, it's just how things are empirically observed to work, we never have anything but one event predictably following another. Yes, we might be able to characterize the chain of events to a lower level of detail, but no matter how much detail we are able to obtain, it's still just a chain of observed events, one reliably seen to follow another, and nothing else.

It is often said today that Hume defeated induction, but that is wildly misunderstanding his argument. As Hume understood, induction is the only way we learn how the Universe works: we observe causal relationships, and model them to anticipate future events. The human brain is wired by evolution to seek out correlations, with survival dependent on being able to correctly do so.

Induction is no more or less than learning from experience. It is limited, in that we can easily be tricked by misleading and false correlations; and more fundamentally, by the fact that our knowledge of how the world works is only as valid as experience shows it to be. An assumed causal relationship could be challenged by the reliable observation of any exception to the correlation -- which puts the burden on anyone who says a particular correlation isn't causation to convincingly show why it isn't. As Hume established, there is no necessary connection in causal relationships, not even in the seemingly obvious collisions of billiard balls. We have, instead, an observed correlation, an observed connection.

* Hume's notion of necessary connection is simple and obvious once grasped, but it's hard to get a handle on the idea. Consider, to reach that end, examples from physics. In the century before Hume, Isaac Newton came up with the law of universal gravitation, which gave the force between two masses as proportional to the product of the two masses, divided by the square of the distance between them. Newton, however, was very careful to say that he didn't know WHY that was so, it was just HOW it worked: "I frame no hypotheses." For all he knew, things could have worked some other way, and then he would have observed something different.

In the 20th century, Albert Einstein expanded on Newton's theory of gravity with the Theory of General Relativity, which defined gravity as the curvature of spacetime. Again, Einstein couldn't say why that was so, it was just a refined description of how things were observed to work. Besides, General Relativity did not discard Newton's theory of gravity, which continues in common use for all but the most exacting and specialized scenarios. Newton had constructed a model that covered all he knew about gravity, and in fact covered almost everything we still need to know about gravity today. Einstein simply built a model that covered a wider range of observations, effectively incorporating Newton's model as a subset.

Neither Newton nor Einstein went beyond what was known from observations. They couldn't. Ultimately, all they could say was how: "That's just the way it is." Why is the Universe the way it is? That's another idle question. The only reply is that if it wasn't the way it is, it would be something different. Silly answer? Yes, but it's a silly question.

We have a tendency to believe our scientific models have a reality unto themselves, but they are only worth anything to the extent they make useful predictions of results. We understand the properties of radio waves very well, but in conceptualizing them, all we have in the mind's eye is a graph of a waveform, the abstracted representation of the radio wave on an oscilloscope or other measuring device. Radio waves don't actually look like that, they don't look like anything; we can't see radio waves with any sort of equipment, we can merely detect them and measure their properties.

Certainly we can, with some confidence, visualize molecules as arrangements of linked spheres, as in the classic chemistry-class models, knowing perfectly well the color codes of different atoms in the molecules are just a useful representation: Well yeah, molecules don't really look just like that, but good enough for all useful purposes.

With somewhat less confidence we can envision atoms, but not as much more than fuzzy balls of different sizes. We recognize that their properties are dependent on the number of protons, neutrons, and electrons that make up the atoms of a particular element -- but any visualization we have of that structure is as representational as the graph of a radio wave on an oscilloscope. The old notion that they look something like a planetary system, with electrons orbiting a nucleus like moons orbiting a planet, was discarded a century ago. Still, the atomic model works; it describes how atoms operate.

Once we get to sub-atomic particles like photons and electrons, we can't visualize them with any confidence at all. We can't ever say what they look like, since they don't look like anything, any more than a radio wave does. What we do know about is their observed properties -- and they make visualization a complete absurdity, since their properties are different in bizarre ways from the "macroscale" objects we can see around us.

For example, electrons and photons have particle or wave properties, depending on what measurements are performed on them. In terms of the macroscale objects we see in our daily lives, electrons and photons make no sense. We have simply established observed connections in their behavior -- and all attempts to show that they do really make the same sort of sense as macroscale objects end up proving they don't.

Why should they? The Universe works the way it does, and we just have to follow along, as dictated by our observations. Attempts to explain why photons and electrons are the way they are go nowhere: they're fundamental particles, never broken down into smaller particles, not made of anything else -- the buck stops there, we have no observations to go any further.

All we have are models of them that amount to sets of accounting rules that describe their behavior. We can understand how electrons and photons are, but we can't explain why they are that way. That's just the way they are. When we run out of observations and reach the end of the causal chain, we can know nothing more, and all we are left with is the inexplicable. There is no infinite regress: sooner or later, we hit the end of the road.

Ultimately, we can't say why the entire Universe is the way it is. Yes, we can break it down into overwhelming detail -- but in doing so, what we learn is how it works, stepping our way through the causal chains one link at a time by observation. We construct models as we go along, and sometimes a model points to the next step; but we don't know if a prediction made by a model is right, until we validate the prediction by observation. Sometimes we don't get the predicted results, and we have to tweak the model to reflect reality. In any case, there's nothing we can know about the Universe except from what we observe of it, and once we run out of observations, reaching the end of the causal chains, we can know nothing more.

* This leads, after the long roundabout, back to the notion of qualia, which ends up being another sort of necessary connection, seeking in qualia an "explanation" of the correlation between brain activity and a reported conscious experience. Qualia, however, are just another aspect of Harvey. Once again, there is no mind-body problem; if certain observed neural activity is invariably associated with a reported conscious experience, then we have understood the relationship between the two.

As a vivid example of this, in 2017 a group of researchers used fMRI and an ANN as a mind probe. Three test subjects spent hours viewing hundreds of short videos, with fMRI measuring signals of activity in the visual cortex and other regions of the brain. A neural network built for image processing then correlated video images with observed brain activity.

Once the ANN worked out the patterns, it was able to predict brain activity as the subjects watched more videos. Going beyond that, through the use of a secondary neural network, the brain activity could show what the subject was watching -- the videos being in 15 categories, such as "bird", "aircraft", or "exercise". The accuracy was about 50% if the system could match the subject to learning earlier obtained from that subject; only about 25% if it could not.

The researchers believe that eventually, given more studies and a much more capable system of neural networks, they will be able to reconstruct images of what a subject is seeing. Again, that wouldn't be like picking frames out of the Cartesian theater inside the brain -- but what else is there to know? What would we "need to know"? The researchers see applications falling out of their work, such as direct brain control of machines, or interactions with paralyzed patients who can't otherwise communicate.

On a more personal level, if Alice burns her fingertip, nobody has any doubt that the neural connection between her fingertip and her brain is the agent for transmitting the sensation of pain to her brain. She feels the pain because of the neural connection; cut the neural connection, she doesn't feel the pain. Of course, how that pain gets routed around her brain is a very interesting question, but one that can be answered by observing her brain activity with, say, fMRI or neural probes.

What more do we want? Yes, if an observed connection seems to contradict established knowledge, we then have reason to suspect we might be suffering from a misunderstanding. However, the trick in understanding the mind is that we have no basis for thinking there's anything going on upstairs except the workings of PONs, because we know of nothing else upstairs that we can establish a correlation with. We have no other phenomenon we can compare the mind to -- or at least we didn't, before we could create machine minds.

BACK_TO_TOP* The notion of qualia leads straight to the notion of the "philosophical zombie", sometimes called a "p-zombie" -- or just "zombie" if the context is understood as "not the brain-eating walking dead". It's a simple idea, a philosophical zombie being a person who seems, by every observable indication, to be conscious; but isn't. P-zombies are what Dennett was referring to with his "zombic hunch".

The first question in this scenario is: how could we distinguish a zombie from the rest of us? By definition, we can't. By the same coin, how could any one of us know that he or she is the only conscious human and the rest of us aren't zombies? That sounds absurd, and Dennett suggested it is. According to Dennett, any being that is capable of conducting itself as perfectly human will be as conscious as any other human.

That is an operational assumption: If we can't tell the difference, we might as well not worry about it. However, it is not just an operational assumption; Dennett took one step farther, pointing out that if we see a perfectly normal human in action and claim that person is a zombie, then we have to ask: What is that person functionally missing? It's missing qualia? There's no Harvey? Well, if Harvey is invisible, who knows if he's there or not? And why care?

The idea that a person who appears to be operating on the basis of a stream of consciousness, but doesn't have one -- instead, somehow operating on a "stream of unconsciousness", as if thinking and consciousness were separated things -- is absurd. There are simply elements of cognition that are necessarily conscious, and cannot be separated from consciousness. An artificial intelligence enthusiast named Eliezer Yudkowsky imagined the p-zombie scenario as ZOMBIES: THE MOVIE, with a substantially altered rendering of his script below:

TEXT:

The atmosphere in the Pentagon briefing room was tense. General Flint broke the silence by announcing: "Bad news, people: reports have been confirmed that New York City has been overrun by zombies."

Colonel Todd replied: "AGAIN?! How many times has that been this year?"

"This invasion's different, colonel. These are philosophical zombies."

Colonel Todd's mouth fell open. After regaining her wits, she asked: "What do you mean, general? They're not shambling, mindless creatures out to devour our brains?"

"No, colonel. They seem exactly like us -- but they're not conscious."

There was a stunned silence in the briefing room. Captain Walters exclaimed: "My god! How insidious!"

General Flint replied: "Indeed, captain. Look at this video -- New York City, two weeks ago." The video displayed crowds on the streets of Manhattan, people eating in delis, a garbage truck hauling away trash. Flint went on: "This is New York City -- NOW." The video then showed New Yorkers on a subway, a group of students laughing in a park, and a couple holding hands in the sunlight.

Colonel Todd was unnerved: "It's worse than I could imagine! I've never seen anything so grotesquely mundane!"

General Flint turned to a lab-coated scientist: "Dr. Cho, what is really going on here?"

Dr. Cho replied: "The zombie disease eliminates consciousness without changing the brain in any way. We've been trying to understand how the disease is transmitted. Our conclusion is that, since the disease doesn't affect ordinary matter, it must, operate outside of the rules of our Universe. We're dealing with a transcendental, immaterial virus."

Captain Walters asked: "Dr. Cho, if the virus is immaterial, then how do we know it exists?"

"The same way we know we're conscious, captain. The complete lack of evidence can lead to no other conclusion."

Colonel Todd was grim: "If we don't stop this virus, civilization will collapse into total normalcy! What can be done, general?"

General Flint replied somberly: "We must act quickly and decisively. We'll send an emergency response team to New York City immediately. Dr. Cho, I need to know what it is they won't be looking for. Follow-on teams will be dispatched to other cities to check for nothing out of the ordinary. It will only be through immediate action that we will have no idea of the extent of this latest zombie invasion!"

END_TEXT [apologies to Yudkowsky for the rewrite]

The notion of a zombie proclaims that cognitive processes associated with consciousness -- perception, thinking, memory -- could exist without consciousness. Consciousness, so such thinking goes, is not only something separate from them; it could also be discarded without interfering with them. However, if consciousness wasn't an inherent aspect of such cognitive processes, if we could function without it, then why would we be conscious?

From an evolutionary point of view, consciousness would have to be judged a product of evolution, a facet of behaviors that enhance the survival and propagation of the human species; if it didn't support such useful behaviors, it would be functionally irrelevant. By the reverse logic, if an entity has all the behaviors, the consciousness associated with those behaviors would necessarily be there as well. We can perceive, remember, analyze, plan, and imagine; all these things imply consciousness, suggesting they couldn't happen without it. That conclusion is reinforced by the pervasive unconscious component of the operation of our brain, further suggesting that we are conscious only to the extent we have to be so.

Indeed, in many circumstances, consciousness is counterproductive: when confronted with an immediate threat, we have to react instantly, without thinking it over. We have some conscious control over our breathing, but for most of the time it's automatic, we don't really think about it. If we had to think about it, we'd be in trouble. We cannot afford the overhead of consciousness except when it's needed.

In addition, in evolution, functionality that isn't useful tends to be "broken" over time by mutations that aren't weeded out by selection -- for example, the non-functioning eyes of cave fish. The cave fish don't use their eyes any longer, and so if a mutation breaks the genes necessary for their function, it causes the fish no harm, and the mutation is carried on to later generations.

If consciousness were functionally irrelevant, if it wasn't necessary, it would have withered away under mutations and been lost in our species. Besides, going back to the notion of a zombie again, if consciousness could break and nobody would notice it was gone, on what sensible basis could we claim there had been anything there to be broken in the first place?

There are those who defend the notion of zombies, saying that if we can imagine them, they could be real. However, we can also imagine that Mickey Mouse lives at the North Pole of Mars with his elves; the only defense that could be made for such a notion is that nobody could prove it wrong -- with the reply that, not being provable one way or another, it ends up being "not even wrong."

If we could build machines that in terms of their behavior are as intelligent as a human but aren't conscious, then we could imagine machines, or for that matter other entities, that are more intelligent, even vastly more intelligent, than we are, but aren't conscious either. Such superior entities might well wonder why consciousness, over which we make such a fuss, is supposed to be a matter of any importance -- but if they weren't conscious, would they be capable of wondering? How could beings that weren't conscious "think things over"?

* Cognitive dualists fall into the trap of qualia -- and zombies -- by failing to realize that a scientific model, once again, is all about observed connections, and that there's no such thing as a necessary connection. The philosopher Thomas Nagel (born 1937) once suggested to Dan Dennett an analogy to the question of qualia by asking the question of: "Why is water wet?"

As Nagel pointed out, that's due to the fact that the water molecule is electrically polarized, which explains many of the interesting properties of water, such as surface tension, its viscosity, the fact water unusually expands when it freezes, and so on.

Nagel's question revealed a failure to understand the distinction between a necessary and an observed connection. Both the polarization of the water molecule and the consequences of that fact, such as surface tension, are all observable and precisely measurable properties. We observed the general properties of water; we eventually learned about the observable -- with the right equipment -- polarization of water molecules; and so established an observable connection between the two, just in the same way that we establish the behavior of billiard balls. Could we have learned of the connection without the observations? How? Do we know anything about the connection except that which is revealed by observations? What, then?

In the same way, if we observe neural activity associated with an experience, we know that activity causes the experience. What more do we need to know? What else can we know? We have an observed connection, we observe no other connection, and there's really no such thing as a necessary connection. A dualist, mesmerized by belief in a mind-body problem, still asks: "How does it do that?" To which a pragmatist replies: "That particular neural activity gives that experience." The dualist remains unsatisfied: "But why?"

The only reply is: "That's just how it is." The dualist could just as well ask: "If we turn on the lights in the room, why is it light in the room?" If the question is not about the functioning of the lighting system, the behavior of light, or the functioning of the eyes -- all of which are HOW questions, that can be nailed down with observables -- then the reply is: "It's light in the room because you turned on the lights, silly." One would be tempted to give the alternative reply: "The Magic Light Fairy did it!" -- but that would be unconstructive.

Dualists cling to a necessary connection, when they can't identify an observed connection: Harvey's just the "little man who isn't there". It's not a question of a false correlation; there's no correlation at all. Humans have a superstitious inclination to invoke "unseen agents" as causes -- failing to realize that, if we observe something completely unfamiliar happening and we don't observe any cause of it, we have no way of knowing what the cause is. We can arbitrarily make up anything we like, but if we can't then observe it, we still know nothing about the cause. It could be anything, but we can't distinguish it from nothing.

The mind-body problem is all about finding a necessary connection between the brain and the mind; but there is no such thing as a necessary connection in any context, we only have observed connections. The lack of an observed connection doesn't imply a necessary connection, it means we just don't know the connection. We assume some necessary connection in the collisions of billiard balls, but that's only because we can see what's going on, and are so familiar with it that we say: "It stands to reason that's the way it has to work."

No, it does not. We never reasoned out that billiard balls work they do; that's just how we empirically observed them to work, and used the observations to devise a model that describes how they work. Nature does whatever it does, and we have to just follow along and take notes. If we weren't familiar with how billiard balls work, for all we know one ball striking another might just back up, pause as if thinking it over, and then aggressively roll forward to hit it again, with the second ball then rolling away. Of course, that would be in defiance of the laws of physics, but:

"What we see is what we get -- what we see is all we get." In nature, there are simply observed correlations that, by virtue of being commonplace, misleadingly seem to be obviously the way things have to be -- when they are, instead, just how things happen to be. A newborn baby doesn't see them as obvious. Nothing at all is obvious to a newborn baby.

* Lest it be overlooked, one other little thing before moving on. There are those who claim the mind is just an "epiphenomenon" of the brain -- that the brain's doing all the work, which is true, while the mind is just along for the ride, and might be thought of as a useless side effect. Or something like that; the idea is vague and difficult to pin down. It appears that what is meant is that the qualia of the mind, as distinct from its observable behaviors, are just useless side effects.

True, the mind does not have an independent existence, any more than a rainbow does -- but a rainbow is still a real-world thing, and we also know that if we have water droplets and sunlight in the right configuration, we always have a rainbow. We might be able to call a rainbow an "epiphenomenon" if we liked; but we would be no wiser whether we did or not. The same thing can be said of the mind. "Epiphenomenalism" founders on the confused basis of dualism: the idea that beings who act aware and conscious may not be so, even though nobody can convincingly show why not.

BACK_TO_TOP