* Having surveyed the history of evolutionary thought and the history of life itself, it is now useful to examine the current state of the science, and assess its strengths.

One of the primary objections to modern evolutionary theory is that unguided natural selection couldn't have produced complicated biosystems. According to this line of thinking, it may be able to produce minor changes, such as antibiotic resistance -- "microevolution" -- but it can't produce elaborate biostructures -- "macroevolution". On investigation, the obstacles to the idea of macroevolution evaporate.

* The evidence of evolution in action is beyond reasonable dispute. As discussed earlier, human selective breeding of domesticated organisms has demonstrated the mutability of species by generating a vast range of forms, some of them with only a faint resemblance to their wild ancestors. Such changes can be very rapid.

A Russian researcher named Dmitri K. Belyaev (1917:1985) set up a program at a silver fox farm to breed more docile foxes, and within a few decades came up with animals that clearly seemed doglike in their appearance and behavior. It appears that a simple change in thyroid action was responsible. Dogs are generally regarded as "neotenous", in other words retaining as adults characteristics of appearance and behavior associated in the cubs of their wolf progenitors, and a similar inability to "grow up" could produce the tame silver foxes. As a control, Belyaev's group bred foxes for savagery, and ended up with paranoid beasts that snarled and leaped to the attack whenever anyone approached them.

Of course, this is an example of artificial selection -- but all natural selection amounts to is saying that the culling of a species by environmental pressures could produce the same sort of results. Species are so mutable that zoo-keepers trying to preserve rare animals find it difficult to maintain captives that really match their wild cousins. Animals that are happy with being captives tend to breed much more easily than those that aren't, and so zoo animals tend to become increasingly tame from one generation to the next -- which still doesn't mean that it's remotely a good idea to walk into a tiger cage.

Consider an experiment: set up a sterile lab environment to prevent contamination, take a culture of harmless bacteria, and then douse it with a toxin that kills the culture off 100% -- no survivors. Repeat this action as many times as desired and get the same results. Now take ten cultures of the same bacteria and administer the toxin in graded doses, from a very small dose to the maximum dose. Take the culture that was given the biggest dose for which some of the bacteria survived, then use these survivors to create ten more cultures, which are given the same treatment. Keep repeating this procedure, and eventually the result will be cultures of bacteria that shrug off the maximum dose of the toxin that would have killed any of its ancestors.

This is a lab experiment, and still somewhat artificial -- though the only way in which it actually differs from the evolution of bacteria in response to a toxin in the "wild" is that the lab experiment screens out confounding influences and makes the process easier to nail down. The same processes occur in nature, the most notorious example being the emergence of "antibiotic-resistant bacteria". The introduction of antibiotic drugs in the middle of the 20th century provided medicine with a powerful set of weapons against dangerous bacterial infections, but even at the time the inventors of antibiotics knew that bacteria would evolve to defeat the antibiotics as they were, and now we are suffering from an ever-rising tide of bacteria that shrug off drugs that would have killed them off neatly thirty years ago.

Another interesting example was the discovery in 1975 of a bacterium that could digest nylon, using an enzyme of course named "nylonase". Since nylon is a completely synthetic material, it would be hard to argue that this capability had been latent in the bacteria; a chance mutation allowed the bacteria to digest nylon, opening up a new "ecological niche" for the bacteria to grow and prosper. Bacteria were later found that could digest polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs).

As far as more complicated organisms go, insects are well known to quickly evolve resistance to pesticides like DDT. For another example, metal electric power towers that are clad in zinc to resist corrosion will form zinc deposits that kill normal grasses and other plants. In fact, most such plants grow perfectly well around the towers -- but on examination they are strains that can tolerate high levels of zinc. Try to bring in plants that grew up far away from a tower, and they will die. There is also the famous example of the rise and fall of the dark form of the British peppered moth relative to the rise and fall of urban industrial pollution. We see evolution by natural selection happening around us all the time.

BACK_TO_TOP* Creationists dismiss the evidence of evolution in action, calling examples such as the emergence of antibiotic resistance "microevolution". They feel it is a jump to think that MET could account for all the elaborations of forms cited by the Reverend Paley, such as the creation of the eye, or in other words "macroevolution". Darwin himself raised this concern in THE ORIGIN OF SPECIES:

QUOTE:

... is it possible that an animal having, for instance, the structure and habits of a bat, could have been formed by the modification of some animal with wholly different habits?

... Can we believe that natural selection could produce ... organs of such wonderful structure, as the eye, of which we hardly as yet fully understand the inimitable perfection?

END_QUOTE

Even if microevolution is demonstrable, does that provide any proof of macroevolution? Isn't it obvious that organisms like bats and organs like the eye had to have been created by some Intelligent Designer?

Richard Dawkins wrote a book titled THE BLIND WATCHMAKER to consider the plausibility of MET, and in one of his discussions in the books he followed up Darwin's comment about the bat, brought up to date. Although it wasn't clearly understood in Darwin's day, many (though not all) bats rely on sonar for navigation, in which a sound is emitted and its echo then timed to range and identify an object. Radar works on the same general concept, though it uses radio waves instead of sound waves. The interesting thing is that bat sonar has so many technical similarities to human radar.

For example, if a jet fighter is operating a radar to search the sky for an adversary, it sends out radio pulses on a fairly long interval -- what radar engineers call a low "pulse repetition frequency (PRF)". This allows a pulse to go a long ways before a second pulse is sent out, giving the radar more range. If a target is identified at attack range, the PRF jumps up drastically, allowing the target to be tracked closely. The common brown bat Myotis will chirp at a rate of about 10 times per second when searching for insects, but this rate will go to 200 times a second when an insect is spotted.

Similarly, a radar usually has a single antenna for both transmit and receive. Since the radio echo is faint, the receiver needs to be sensitive -- but without protection, the powerful transmit pulse will tend to fry it. The trick is to use a "diplexer" that shuts off the antenna receiver path while the transmit pulse is being sent. The Myotis bat has sensitive ears to pick up its ultrasonic chirps; a special bone mechanism shuts down the ear channels while a chirp is being emitted, so the bat won't deafen itself.

The Myotis bat even has an ability that nobody clearly understands to sort out echoes of its own "voice" from those of others -- the bats tend to live in colonies, sometimes dense ones, and have no problem navigating in the dark when dozens of other bats are in flight nearby and are filling the darkness with their chirps. Bats also appear to jam the calls of other bats.

* How could anyone believe that something as elaborate as bat sonar could arise by natural selection? Creationists insist that macroevolution cannot account for bat sonar and other elaborations of organisms, and have attempted to show why. However, their examples have much less demonstrated any failure of MET than a failure to understand it.

One common tale presented in a number of variations to illustrate the gulf between microevolution and macroevolution is the "canyon" story. The premise is that there is a deep, impassible canyon -- representing an evolutionary jump -- between a woman named Alice and a neighbor named Bob. If the canyon is very narrow, Alice can simply jump across (microevolution). Now suppose that the canyon is extremely wide (macroevolution). Alice can't just jump across; what MET claims, as creationists have it, is that Alice managed to get across the gap by jumping across a series of mesas in the canyon. It took her a very long time, of course, and the mesas eroded away behind her and left little or no trace, implying the sketchiness of the fossil record. The scenario shows that macroevolution is a ridiculous concept.

It must be emphasized that analogies are useful as illustrations, but they don't constitute proofs of anything in themselves. Simply because two unrelated things resemble each other in some respects does not mean they are similar to each other in others. Analogies are only as valid as their correspondence to reality. In this case, the correspondence is broken because the story conjures the notion of an obstacle, an "impassible canyon". In evolutionary terms, this is a contrivance: "Huh? Obstacle? What obstacle?"

Evolution works one step at a time, moving from one useful adaptation to another, following the line of least resistance over the adaptive landscape. If Alice and Bob are only 100 meters apart (microevolution), Alice can walk over in a few minutes. If the two are 10 kilometers apart (macroevolution), Alice will take a day to walk over and visit Bob. Even if they're a thousand kilometers apart, Alice can get there in a hundred days. The creationist argument of microevolution versus macroevolution amounts to saying that it's absolutely inconceivable that Alice could walk a thousand kilometers in a hundred days -- and so, she must have teleported by some unexplained means.

* A similar but even more contrived tale posed by creationists considers the possibility of a prairie dog crossing a busy highway. If the highway only has two lanes or four lanes (microevolution), the probability of a prairie dog getting across is reasonable. However, suppose that the highway has a thousand lanes (macroevolution): the prairie dog has zero chance of making it across alive. Macroevolution is now shown to be impossible.

The tale of the prairie dog is interesting because its correspondence to the actual details of how evolution works is completely muddled. It is also interesting in that revising the story to get rid of the muddle provides a tidy, if cartoonish, example of how evolution actually works. Let's modify the scenario by envisioning a whole colony of prairie dogs on one side of a thousand-lane highway, and adding habitable dividers between the lanes.

Suppose the prairie dogs completely strip the side of the highway they are living on of plant life. They now have a choice of staying where they are and starving, or crossing a lane of the highway to the divider. The colony gradually migrates across the lane, losing a proportion of their number in the process, and sets up home in the divider, raising a new generation. The new generation of prairie dogs strips out the divider; since the side of the highway that their parents came from is still barren of plant life, all they can do if they want to survive is migrate across the next lane.

This process is repeated for a total of a thousand generations, when the prairie dogs finally reach the far side of the highway. In the final crossing, not at all incidentally, the proportion of prairie dogs killed is substantially smaller than the proportion lost in the first crossing: the slow and the stupid were run down over the crossings and eliminated from the gene pool. This is how evolution works: whole populations undergo selection pressures over a number of generations. The scenario also parallels reality in that it takes a long time, a thousand years or more, for the prairie dogs to get across, and in the process many "losers" end up being left on the highway. If there were an indefinite number of lanes, sooner or later the descendants of the original prairie dogs would have the skills to cross the lanes without any particular difficulty.

There is no more inherent distinction between microevolution and macroevolution than there is between "microwalking" across a room and "macrowalking" a thousand kilometers. It just takes longer.

To be sure, some evolutionary adaptations are of much more far-reaching significance than others -- one of the best examples being the emergence of sexual reproduction, allowing the selective combination of genes between two organisms, a demonstration of the "evolution of evolution" -- but the fact that some innovations have more impact than others doesn't change the basic argument in the slightest.

In addition, if the probability of a drastic macromutation being beneficial is slight, that means that there's still a long-odds bet that it actually will be. Functional macromutations may well be an infrequent but potentially significant feature in the evolution of life -- every rare now and then, the "evobot" will be able to jump and end up on higher ground in the fitness landscape. Some believe that it was such rare evolutionary leaps -- the bigger the leap, the more proportionally rare its occurrence -- that were responsible for some of the major innovations in the evolution of life.

There are also some mutations with large-scale effects that aren't all that troublesome and which are clearly demonstrated by the evidence. As discussed later, there are master control genes that direct the construction of an organism from its various structural "subunits", and sometimes they can increase or decrease the number of subunits -- for example add or delete a new set of ribs. Snakes have hundreds of ribs, far more than their four-legged lizard ancestors, and obtained these ribs through mutations in control genes that specified the construction of more rib subunits. Richard Dawkins calls such mutations "stretched jetliner" mutations, along the lines of the way jetliners are often redesigned for higher capacity simply by inserting a fuselage extension or "plug" before and after the wings.

As Dawkins points out, in such mutations the basic arrangement of the organism is retained, just as it is in a stretched jetliner, with no requirement for any major reorganization of the organism to compensate for the change. Along the same lines, early fossil squids had only two tentacles; obviously, they acquired their modern profusion of arms and tentacles by duplications. The discovery of master control genes has suggested that evolutionary modifications along the general lines of stretched jetliner mutations are actually more general and important than previously thought.

* Incidentally, this argument does not claim that evolution by natural selection never runs into obstacles. Envision a colony of prairie dogs and a thousand lane highway without dividers. When the prairie dogs strip out the vegetation on their side of the highway, their only choice is to try to cross the highway or starve.

What happens? The answer's obvious: they all die. This presents no challenge to MET: extinction happens all the time -- nobody sees velociraptors running around any more, except in the movies -- and in fact Darwin himself described extinction as an important background element of his case, since it implied the succession of species. A species may simply not be able to adapt to changes in its environment; the species has no means of "willing" the necessary mutations needed for survival, no matter how desperate the circumstances.

The shifting fitness landscape actually can set up barriers, either channeling evolution in particular directions or setting up traps from which there is no avenue of escape. This is demonstrated by the mass extinctions of the past, particularly the Permian extinction, when a very high percentage of species died out. In MET, species can be expected to go down blind alleys and hit dead ends, over and over and over again.

BACK_TO_TOP* There is another aspect to the objections to macroevolution, in that creationists inevitably assume destiny: that a particular complicated system needed to perform a function was a preconceived Intelligent Design, and so the odds of it happening by natural selection processes were vanishingly low. However, under natural selection a range of possible systems might well have arisen to perform the action, and the one that did emerge was only one of the possibilities.

Alice wasn't actually planning to walk over to Bob's house, she was just following the path in front of her that seemed easiest with no particular final goal in mind, and Bob's place is where she happened to end up. She ended up at Bob's house, she might have just as easily ended up at Zelda's house. The probability that sooner or later Alice was going to end up someplace was, barring misfortunes, one.

The American philosopher Daniel Dennett (1942:2024) expressed much the same idea in terms of a con game:

These 32 gamblers have been handed the right call on a football match from Bob five times in a row and think he has a miraculous ability to predict the future. Bob then says he will give the 32 gamblers the results of the next game ... but only if they each pay him big money first. The suckers don't realize that Bob never predicted anything -- they're only see the successful calls, and don't realize there were many more dead ends.

In more general terms, creationists are falling into what is generally known as the "prosecutor's fallacy". If somebody wins the big lottery, a skeptic might just as easily say that since the odds of winning are extremely low, there was no way that the winner could have won by accident: the lottery had to have been rigged by someone. The reality is that somebody wins, it's just impossible to figure out who it will be ahead of time in a fair lottery. Evolution tends to produce a solution in response to selection pressures, but it produces any solution that works.

There's nothing pre-ordained in the organisms that now exist on the Earth; all that can be said about them being the way they are is that if they weren't, they would be something different. As the pioneering mathematical biologist D'Arcy Wentworth Thompson (1860:1948) commented, capturing the banality of the idea: "Everything is the way it is because it got that way."

* In any case, on close examination, the supposed obstacles to macroevolution evaporate. Why can't a thousand microevolution events make up a macroevolution event? If provable small changes can occur over a short period of time -- or maybe even not so small, such as the emergence of a pekinese from its wolf ancestor -- what no good reason is there to think that many small changes over a long period of time can't add up to big changes? Even arguing that some of the changes are improbable doesn't shoot down the idea, since what is improbable over a short period of time becomes a certainty over a long period of time. If we didn't age and were indestructible, then we could bet that we would be struck by lighting every rare now and then.

By analogy, languages are known to evolve -- try reading Chaucer. Two separated populations of people speaking the same language will gradually develop different dialects over a period of time. Obviously, the two dialects will diverge over time, through small gradual changes, until they are mutually intelligible and have become distinct "species" of languages. Dutch speakers, for example, generally cannot understand Afrikaans even though both languages share the same primary linguistic roots.

Of course, the evolution of organisms and languages are not the same thing, one major difference being the inclination of speakers of a language to adopt words and syntax from other languages. However, that's not so different in concept from the way bacteria can acquire genes and traits from other kinds of bacteria through "horizontal gene transfer", and overall the analogy between the evolution of organisms and languages is a strong one.

In particular, as a rule languages are not "intelligently designed", according to some top-down plan; they have many functionally nonsensical features, for example the insistence of many languages on arbitrarily assigning genders to all nouns, including those pertaining to inanimate objects. They can, however, be said to be "designed" in a bottom-up fashion, with individual speakers deciding how they want to say things, and the rest of the population of speakers deciding if they want to go along with it. The result is effective but not all that orderly, not neatly thought out as a system. This is also a characteristic of biological evolution.

BACK_TO_TOP* The analogy between the evolution of organisms and of languages is strong enough to pose the question of why there is, must be, some sort of "magic barrier" to the emergence of a different species through a process of gradual mutational change. After all, nobody can show there is any "magic barrier" to the emergence of a new, clearly distinct language through a process of gradual change.

What creationists are saying in their belaborings of the macroevolution issue is, roughly: "MET can only do 1% of the job." To which the answer is: "But if it does 1% of the job a hundred times, then it completes the job." Again, as Darwin put it, "naturum non falcit saltum" -- evolution does not work by big leaps, it's just one little step at a time in an indefinite series of steps over millennia. The problem with creationists is that they are not merely saying that MET does 1% of the job, they're saying it does 1% -- and then stops, to never evolve another 1% again, blocked by a "magic barrier".

The reality is that, over time, the accumulation of small changes adds up. Albert Einstein was once supposedly asked: "What is the most powerful force in the Universe?" He replied: "Compounded interest." A small amount of capital left in the bank drawing interest and increasing its size will sooner or later become a great fortune. A small rate of interest and growth simply means that it will take longer.

Darwin had a hobby of raising pigeons, acquired originally as something of a research project in domesticated animals, and observed something equivalent to this notion in the selective breeding of his domestic pigeons. He observed how an enormous range of variations in pigeon form had been created from, as he believed, a single wild species, the rock pigeon. Not all pigeon fanciers believed this, but he observed "that most skillful breeder, Sir John Sebright, used to say, with respect to pigeons, that 'he could produce any given feather in three years, but it would take him six years to obtain head and beak.'" Sebright in effect simply bred to accumulate small changes until he got what he wanted.

In deep time, even the slightest rate of interest builds up massively. Consider investing a dollar at an interest rate of 1% per century -- that is, after a hundred years, the dollar earns a penny of interest -- and then re-investing the result at the same rate. In a million years, not a long period of time on a geological basis, the investment would grow to 1.01^10000 == 1.64E43 dollars. Assuming that the money was in the form of $1,000 bills and very conservatively estimating that a stack of ten thousand such bills weighed a kilogram, then this quantity of money would amount to 1.64E36 / 1.99E30 == 800,000 times the mass of the Sun.

Applying this reasoning to organisms and the evolutionary growth of complexity is tricky, particularly because nobody has ever come up with any general way to assign a numeric measure of complexity to an organism. However, that difficulty cuts both ways: creationists don't have a good definition of what "complexity" means, or explain how complexity makes a problem for evolution. Consider various aspects of complexity:

A complex system can be broken down in simpler elements; if it couldn't, we wouldn't regard it as complex. By the same coin, the basic elements of a system are necessarily simple, with levels of systems of increasing elaboration built up to create the complete system. If we recognize that the simple elements of a biosystem can evolve, then there is no difficulty in believing the entire biosystem evolves through the evolution of its interacting simple elements, there being nothing in their interactions that presents a problem. If the elements of a biosystem each "microevolve", then overall their effects may well be the "macroevolution" of the entire organism.

On a more fundamental level, creationist objections to MET over complexity amount to an unjustified assertion, proclaiming that things exist in nature that, for some vague reason, shouldn't -- like saying that rain should be expected to fall up, not down, and why it falls down is inexplicable. Our observations clearly show that complex organisms are a part of nature, just as certainly as we observe that rain falls down, and so it is hard to understand what reason we would have to consider them "unnatural".

In the era before modern biochemistry, some thought that life itself could not be accounted for by the laws of nature, that there had to be some "life force", an "elan vital", no mystical "life force"; now we know there's just biochemistry. Having conceded defeat on that score, creationists have been forced to retreat and insist that the origins of those complex organisms are unexplainable in terms of the laws of nature.

In the extreme, the insistence on a "magic barrier" amounts to a transparent ploy, insisting that small-scale evidence from short-term observations is unconvincing -- and then declaring that there is no "convincing" evidence except direct observations over long timescales for which, conveniently, direct observations are ruled out on the face of it: "Were you there? Did you see it? Then how do you know?"

As far as the criticism that pekinese and wolves are still the same species goes, biologists can turn the criticism around. Dogs and wolves differ genetically only by about 1%; if that much alteration can be obtained from 1% variation, how much alteration could be obtained from, say, 5% variation? The physical variation between dogs and wolves shows just how plastic and life really is -- indeed, analysis of the variation in structure of dog skulls shows they vary more among themselves than do the skulls of the entire order of carnivores. Of course, it can be pointed out that changes beyond that 1% level would eventually undermine the genetic compatibility of the descendants of pekinese and wolves to the point where they cannot interbreed even in principle. Even Darwin, with his weak comprehension of heredity, understood that the divisions between species are gradual.

In fact, it would actually take intervention to prevent the gradual emergence of species. Populations undergo genetic shifts over time, even by simple neutral genetic drift; unless some agent puts a stop to the drift somehow, eventually the shifts between the two populations will accumulate to the extent that they can no longer interbreed. Genetic shifting could be compared to the erosion of, say, a beach under wave action: it doesn't matter how slow or fast the rate of loss of the beach is, sooner or later the beach is going to be eroded away. Similarly, genetic shifts will gradually erode away the ability of the two populations to reproduce with each other.

* As a response to those who declare macroevolution preposterous on the face of it, it can be pointed out that MET isn't really much more preposterous than, and in some respects is conceptually similar to, the notion of free market economics, the idea that commerce tends toward efficient operation even without rigid centralized control. A consumer demand will lead to the emergence of producers to meet the demand; prices will reflect the scarcity of products; and inefficient producers will go broke.

In this process, both consumers and producers are basically only concerned with their own interests in economic transactions; neither is seriously concerned with the operation of the system as a whole. Centralized planning does not control the process. There is a story that during the era of the Soviet Union, there was a belief among some senior Communist officials that there was no conceivable way market economies could be really more efficient than a centrally-planned economy. Clearly, there had to be some secret organization that was controlling things, they were mistaken.

Human activities are not always controlled from the top down; very often, organized activities emerge from the bottom up, by the convergence of people in a group working towards common goals. Goals may be set from the top, but in any case people get ideas, then work out among themselves how to get things done, with rules and structure emerging in response. Yes, that can be a messy process, but it is much more workable than top-down directives thrown at people without real consideration of the realities they have to deal with.

BACK_TO_TOP* One of the most significant examples of macroevolution is the evolution of the eye. Creationists find it most implausible that the eye could have been produced by evolution -- Paley used it as an example of "Intelligent Design" -- there is plenty of evidence that the eye did evolve in a sequence of steps, from an early or "primitive" state.

It actually seems unlikely that there were ever many multicellular organisms that were completely blind. There are plenty of organisms in modern times -- some jellyfish, starfish, various kinds of worms -- that have nothing resembling an eye but have skin that can sense light, in much the same way that we can locate a heat source just from sensing warmth with the skin on our hand.

The next step is to obtain a simple eyespot. The trick is to have chemicals in a cell that are modified by light and that can trigger a nerve ending. Once a one-celled eyespot is available, it can be duplicated, roughly doubling the amount of light that can be picked up. Similarly, the individual cells in the eyespot can be enhanced to increased their sensitivity, and they can also be layered to pick up more light.

An eye arranged as a simple array of light receptor cells can have high light sensitivity, but it has no directionality. One simple way to improve on matters is to arrange the array inside a cup. All this really does is narrow the field of view, giving the organism better directionality if not resolution. The deeper the cup, the better the directionality. Cup-shaped eyes of a range of depths are common in the animal kingdom, with examples including flatworms and clams.

The cup-type eye still can't form an image on the array of light receptor cells. Now suppose the entrance to the cup shrinks down to a mere pinhole; the structure will then act as a "pinhole camera", casting an image onto the light receptor array. The squidlike chambered nautilus is well known for its pinhole camera eye.

The pinhole camera eye of the nautilus is open to seawater. It would help protect the interior of the eye if it was filled with some transparent substance and maybe covered with a relatively tough transparent film. Such eyes do exist; beyond that, the film can evolve into a lens, providing a wider aperture to admit more light, and to focus an image.

Now we have the basics of a camera-type eye like our own. Our eye also includes a capability for changing the focus of the eye, a pupil to cut down the light admitted under bright conditions, and of course means of rotating the eye in different directions. We also have a fair chunk of our nervous system devoted to picking up and interpreting imagery obtained by our eyes. It is no more difficult to conceive of how these "accessories" could have evolved than it is to conceive how the eye itself could have evolved.

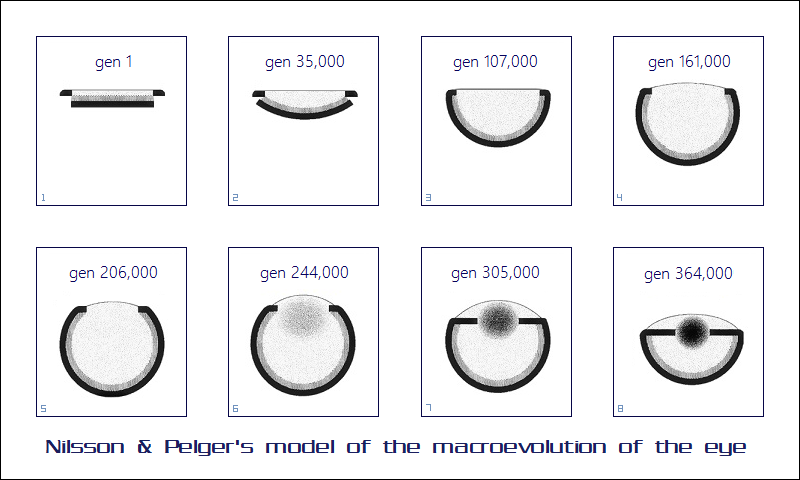

In 1994, two researchers, Dan-Erik Nilsson and Susanne Pelger of the University of Lund in Sweden, published a paper describing an analysis they had performed, in which they envisioned the evolution of a fish eye from a simple eyespot by steps of almost imperceptible 1% changes in various component parameters. The analysis was based on conservative assumptions; it determined that it would take 1,829 steps to go from a simple eyespot to a fully-developed fish eye, and that this could happen in about 364,000 generations.

The paper took the existence of an initial eyespot for granted, but this is not seen as a particular challenge: a simple eye can consist of nothing more than a nerve cell coupled to a skin cell loaded with a photosensitive pigment. Initially, the pigment might not have been all that efficient, but in time natural selection could be expected to improve on matters.

* The idea that the eye evolved is enhanced by the fact that there is great diversity in the construction of eyes. There's wide variation among organisms with camera-type eyes; birds of prey, which have to scan the terrain for targets from above, have eyes with much better resolution, as well as the ability to focus rapidly to ensure they can keep on target in a fast dive. Spiders have camera eyes along the lines of our own; jumping spiders have tiny eyes but have achieved relatively high resolution vision through a dodge. Their retina is not in the form of a sheet, but organized as a vertical strip. To get a better image, they simply vibrate the strip back and forth.

Naturally, creatures that operate at night, like a cat, have adaptations for seeing in the dark. Many nocturnal animals have a reflecting backing to their retina called the "tapetum lucidum". It bounces back light that would otherwise have passed through the retina and been lost, improving sensitivity. Cat's are the best-known example of animals with a tapetum lucidum, which causes their eyes to gleam in the light of car headlights. Certain kinds of spiders also have a tapetum lucidum.

However, some nocturnal animals don't have a tapetum lucidum, most notably the South American owl monkey and the Old World tarsier -- with the result that they have oversized eyes. It might have been nice for them to get a tapetum lucidum, but they didn't win that prize in the evolutionary lottery.

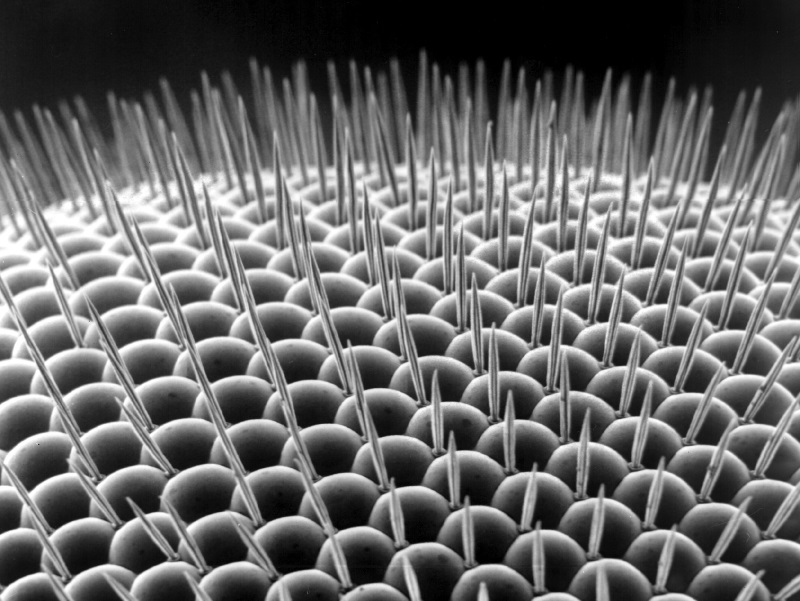

There are also radically different schemes of eye construction, the best example being the compound eye of the insect, which is an array of simple tubular eyes, or "ommatidia", arranged over a hemisphere. The compound eye provides fair resolution and a better overall field of view than the camera eye. The compound eye is so different from our own camera eye that it is a bit difficult to imagine exactly what an insect sees with it. Observations of insect behavior suggest that at least in some cases the compound eye simply acts as a wide-field motion sensor to give warnings of threats, and to allow the insect to track and assess prey.

The compound eye is definitely limited by the amount of resolution it can obtain. A dragonfly eye may have 30,000 ommatidia, which sounds like a lot, but to match the resolution of our own vision it would need millions of them. To even approach the quality of our vision would require compound eyes the size of beachballs.

In some respects the compound eye seems a evolutionary dead end, and it's not found in many animals other than insects, and their relatives the crustaceans. So why haven't they evolved "proper" camera eyes like their arthropod cousins, the spiders? That's because evolution doesn't work in such a deliberative fashion. The insects and crustaceans went down a particular branch of eye development, and they acquired an eye that does the job for them well enough.

However, is the compound eye really a dead end? Again, there are no "magic barriers" in evolution. Consider the insect named Xenos peckii, of the obscure order of Strepsiptera, which are parasites of other insects. X. peckii is a parasite of paper wasps. An X. peckii female never leaves a wasp host, and never fully develops, lacking wings or legs or eyes; she lays eggs that hatch and grow into juvenile forms that migrate through the wasp nest, to infest wasp grubs. The grubs mature into wasps, carrying the parasites; the male parasites will mature into a flying form, which will force its way out of the wasp's body to seek a female, which partly emerges from its host and emit pheromones -- attractive odorants -- to tip off the males.

The males don't have mouth parts and can only live for hours, so they are under a fast clock to find a female and mate with her. To this end, X. peckii males have eyes that seem to be compound eyes at first glance -- but on second glance, instead of a dense array of hundreds of ommatidia, they end up having a sparser array of camera-type eyes, with about 50 eyes each. This gives a handy compromise, with a wide field of view combined with relatively high resolution. On finding a female, the male mates her, then dies; the female retreats back into her host, to begin the cycle all over again.

Nilsson also pointed out an example of a creature that originally had a compound eye scheme, but which evolved into a camera eye scheme. Some deep-sea crustaceans, living in eternal near-darkness, have simplified compound eyes, the ommatidia having lost their tubes with the eye reduced to a simple array of photosensor cells. One crustacean named Ampelisca actually does have a camera eye, uniquely or nearly so among crustaceans -- but the retina is clearly derived from an array of stripped-down ommatidia. The speculation is that the ancestors of Ampelisca went through a deep-sea sequence that caused their compound eyes to degenerate. Ampelisca itself does not live in the dark depths, and in its adaptations to an environment where there was more light available, it redeveloped the eye along the camera path. One step back, two steps forward.

BACK_TO_TOP* One of MET's key concepts is the notion of a selection process. Richard Dawkins created a simple and interesting computer simulation that suggests just how powerful a selection process can be. To simplify the discussion, consider the name:

CHARLES DARWIN

That string consists of 14 characters, including a space. Suppose a computer program was written to simply throw together characters and see if the result matched the name of CHARLES DARWIN. How long would it take to come up with a winner? Given 26 Roman capital letters and a space character, the number of possible strings of 14 characters is 27^14 = 1.09E20. Assuming that a computer could generate and test a million strings a second, on the average a match would be found only about once in 3.5 million years. For every character added to the string to be searched for, the time would increase by a factor of 27.

Dawkins suggested another approach:

This description gives the number of strings, or the number of "progeny" per generation, as a dozen, but it can be any value greater than one, and most modern implementations of this program allow the user to set the number of strings. A trial run of a variant of this program, using a progeny size of a dozen and only providing status output every 50 generations, ran to completion in 3 seconds after 4,318 generations.

This program is a simple-minded example of what is known as "genetic algorithm". It is straightforward for a computer to make small changes at random, test them, and quickly converge on the answer. This program is generally known as "Dawkins' weasel program" since he used the text example METHINKS IT IS LIKE A WEASEL, that being a citation from HAMLET that Dawkins used in THE BLIND WATCHMAKER to mock the notion that MET was like claiming that a gang of monkeys pounding on typewriters forever could produce the works of Shakespeare -- the "monkeys & typewriters" scenario -- which actually can be loosely regarded as a model of saltationism. A "monkeys & typewriters" or "saltationist" program written along such lines would simply keep generating strings of 14 random characters until a match occurred, which as shown might take a very long time.

* The weasel program is flatly a toy, one that any amateur programmer with an ordinary level of skill could put together in a few hours, and in fact purists get annoyed at labeling it a "genetic algorithm". Such programs usually perform "crossbreeding" of optimal solutions for every generation to help converge on the solution faster -- it should be noted that the weasel program can be and has been modified to incorporate crossbreeding.

In any case, genetic algorithms are in expanding practical use for the solution of problems that would frustrate a "brute force search" by a computer. The US National Aeronautics & Space Administration (NASA) wrote a more sophisticated genetic program to determine the optimum design for a small radio antenna, ending up with a piece of bent wire that looked like something a hopelessly bored schoolkid in a dull class would make out of a big paper clip.

One of the interesting things about genetic algorithms, is that they can actually produce results that nobody anticipated. In the case of the antenna, the program itself had -- just by blindly following its evolutionary rules and through no other intelligence -- designed the antenna itself.

It must be emphasized that such programs are not really models of MET as such, the weasel program demonstrating an artificial selection process, with a specified end goal that MET says doesn't exist. It is no great challenge to write programs that do demonstrate natural selection.

In his book CLIMBING MOUNT IMPROBABLE, Dawkins discussed a set of programs that model spiderwebs. Spiderwebs are an excellent subject for evolutionary modeling: they are surprisingly elaborate constructs that are complicated to build, amounting to a considerable feat for purely instinctive creatures such as spiders, while being simple in comparison to other biostructures such as the eye. They are certainly simpler than the spider -- though they are effectively part of it, an "extended phenotype" of the spider.

The simulations began with a "web" consisting of a few sticky strands that was then modified in random ways, with the webs that turned out to be more effective at trapping flies retained and the failures discarded. Ultimately, they produced spiderwebs much like those of real-world spiders.

Incidentally, creationists claim that evolutionary simulations are proof of "Intelligent Design", since they are computer programs created by an intelligent (human) designer. This assertion sounds logical for about three seconds, until it's realized it's along the lines of the old cartoon gag in which a tunnel is painted into the side of a mountain -- and a train immediately comes roaring out. It's a confusion between models and the things they're supposed to represent, like saying that if a toy robot panda is built by a factory in China, then a real panda must be built by a factory in China as well.

If we construct an origami fox out of a piece of paper, then if we reason by analogy that real foxes are also constructs -- we can just as well reason by analogy that they're made out of paper. The "paper fox fallacy", to give it a name, is popular among creationists, who refuse to realize they are claiming that if humans imitate nature, then of course nature must be imitating humans. If humans make a fire, does that mean that fires must be "Intelligently Designed", too?

Computer simulations only reflect the information that was put into them; it is possible to write a simulation of, say, tornadoes or planetary orbits, but tornadoes and planetary orbits are easily explained by the known laws of nature -- nobody believes the old notion that planets are pushed along their paths by angels any more. It can be claimed without contradiction by the evidence, or confirmation by it, that the entire Universe is maybe something like a computer program written by some higher power, but that amounts to no more than a premise for a sci-fi story, or the theology of UFO cult.

Of course, the fact that simulations are artificial models of the real world also demonstrates their unavoidable, acknowledged limitation: once again, no model of the real world is any more valid than the assumptions on which it is based, and the conformance of its results to observations. In recent years there have efforts to write very elaborate "artificial life" computer programs to provide broad simulations of life and its evolution -- but this is a very ambitious goal, possibly too ambitious. Work continues.

It should also be pointed out that, though human artifacts are intelligently designed, technology evolves, generally through small improvements, with some great leaps when imaginative new inventions emerge. Furthermore, by definition artifacts are products of humans, who are products of evolution. Just as the spider web is an extended phenotype of the spider, all human artifacts are an extended phenotype of humans. In an attempt to trace back origins to Intelligent Design, in the end we find "evolutionary design" instead.

BACK_TO_TOP